Big Data and Tiny Type, 1960

A meteorologist demonstrates the use of a handheld microcard reader, probably at the National Weather Records Center in Asheville, North Carolina. “This model is convenient for examining microcards quickly or for checking for one particular entry, but is not suitable for prolonged use.” A more suitable device is pictured below. (Image and quotation from William M. McMurray, “IGY Meteorological Data on Microcards,” IGY General Report Number 9, June 1960, pp. viii-ix.)

Every year, the History of Science Society puts out a journal devoted to one theme that cuts across the history of science. This year it’s “Data Histories,” stories of how huge amounts of scientific data have been amassed, managed and used in fields as diverse as ornithology, paleolinguistics, bibliometry and astronomy. The article that caught my eye first was Elena Aronova’s story of managing the observations taken during the International Geophysical Year (an eighteen-month period spanning 1957-58).

Aronova makes a fascinating argument about the role that geophysical data played in Cold War politics. But here, I just want to follow her story about the practical challenge of dealing with huge amounts of data before the digital age.

“Remember the IGY was a big data collecting binge,” said Alan Shapley, a chairman of the US’s IGY organizing committee. The hangover after this binge was literally millions of pages of observations of all kinds of geophysical phenomena. Ocean currents and weather conditions, auroras and earthquakes, geomagnetic and gravimetric observations were among the aspects of the Earth measured and recorded by thousands of scientists working across the globe. As Aronova puts it, “the IGY’s announced aim was the creation of a data archive that could be mined endlessly, for future uses not yet known.” Maybe it was the hangover, not the binge, that organizers actually wanted.

But how to preserve that data and make it accessible to researchers? IGY planners expected that computer processing methods would soon be widely used, Aronova notes. But punch cards couldn't compress data small enough to circulate data around the world. The World Meteorological Organization estimated that one complete set of IGY weather observations would require 50 million punch cards!

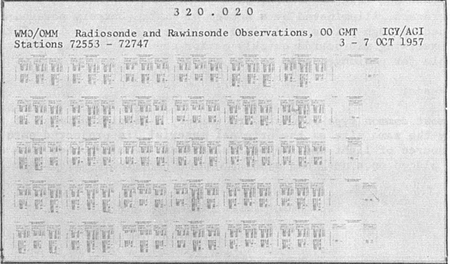

Microphotography offered a solution. Using specialized cameras and high-resolution dye-coated paper, 96 pages of text could be reduced to a single library catalog-sized card. This form of analog data compression allowed the meteorological observations to fit on just 18,500 cards, held in a reasonably sized cabinet. Plus, microphotography made it easy to capture the non-numerical forms of data as well, including maps, spectrograms, all-sky camera photographs, and “visoplots,” a standardized form devised for the IGY to record data on auroras.

A microcard recording many pages of upper air observations taken between October 3 and 7, 1957. (From William M. McMurray, “IGY Meteorological Data on Microcards,” IGY General Report Number 9, June 1960.)

While this system sounds exotic now, Aronova describes how it was derived from a technological system familiar to many people during World War II. The US and British deployed microphotography to manage the great quantities of letters sent between soldiers deployed around the globe, and their families at home. Senders wrote letters on standardized “V-mail” forms, censors approved them, and then they were filmed and shipped via airmail, with 150,000 letters packed into a single mailbag. Letters were then reprinted and delivered to recipients in a size readable with the naked eye.

But IGY raw data was not reprinted for ease of use. Instead, researchers accessed the data through specialized display devices. For the meteorological records, that meant using microcard readers, either handheld devices like the one pictured above, or a less eye-strain inducing desktop reader pictured below.

A magnified image of the microcard, approximately the same size as a the original, is projected onto the screen. Knobs allow the user to move between pages printed on the card. (Image source: William M. McMurray, “IGY Meteorological Data on Microcards,” IGY General Report Number 9, June 1960, p. viii.)

Unfortunately, the IGY’s goal of creating a mine for future knowledge was largely a failure for scientists. Aronova argues the World Data Centers prioritized accumulating and exchanging data, rather than analyzing and using it. While sophisticated archival systems for cataloging, retrieving, and even searching microfilm were developed, they promised much more than they delivered.

The significance of the IGY’s “data history” lies elsewhere. The push to make geophysical data open, shareable, and international, even amidst the tensions of the Cold War, contributed to norms that still guide how we study and govern the global environment. In contrast to the secrecy that has often characterized nuclear data, data on weather, climate, and the Earth’s magnetic environment has generally been viewed as a public good that should be accessible for the benefit of all.

Learn More:

- Elena Aronova, “Geophysical Datascapes of the Cold War: Politics and Practices of the World Data Centers in the 1950s and 1960s,” Osiris v. 32 (2017): Data Histories: p. 307-327.

- William M. McMurray, “IGY Meteorological Data on Microcards,” IGY General Report Number 9, June 1960

- Victory Mail: Resizing Lifelines. National Postal Museum, Smithsonian Institution. Online Exhibit.