The Tornado Research Aircraft Project

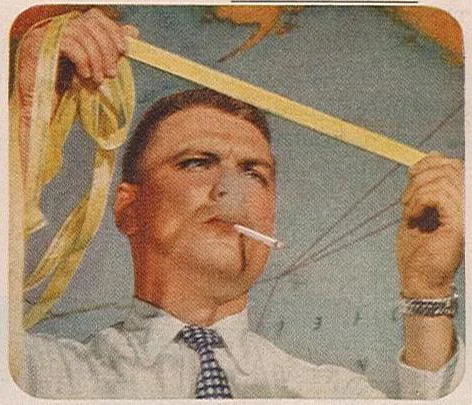

Loose photographs stink. A war-surplus P-38 Lightning, labeled “US Department of Commerce Weather Bureau Tornado Research Project,” circa 1958 or 1959. Someone has written “To Jack Stony, Aug. 1939” on this fading color print I acquired through eBay. Without an archival collection to give a loose photo some context, it’s difficult to understand its significance--even when it’s obvious what’s in the picture. Who is Jack Stony, or perhaps Jack Story? Who gave him this color print? Why did they write Aug. 1939? Could the '39 be nothing more than a slip of the pen? Image from my personal collection, photographer unknown.

American meteorologists enjoyed an easily overlooked advantage in the decades after World War II: ready access to high performance airplanes and trained pilots to fly them. Sometimes the military contributed planes and pilots for joint research projects, like the Thunderstorm Project in 1946-47, or Project Stormfury during the 1960s. But there were also significant numbers of surplus warbirds left over from World War II, and private pilot/owners eager for contracts.

Take the Tornado Research Aircraft Project. Beginning in the spring of 1956, a hotshot pilot named James M. Cook flew his P-51 Mustang out of Kansas City in search of severe thunderstorms. Cook was contracted by the US Weather Bureau, which supplied special instruments for his planes, to explore promising storms that could help forecasters understand when and how tornadoes formed. Cook had previously used his planes for cloud seeding, so he’d developed considerable expertise in navigating thunderous skies.

It could be a hairy ride. As Chester Newton, the chief scientist for a later incarnation of the project remembered, Cook “liked exciting experiences and he managed to find the parts of the storm, he had an instinct for this, where you could both get measurements and have some fun, and have the life scared out of you at the same time.”

Cook switched to the P-38 pictured above in 1958, while Chester Newton remembered flying with Cook in an A-20, a heavier twin engine attack plane also left over after WWII.

The project expanded dramatically in the fall of 1959, as the Weather Bureau brought in the Air Force, Navy, FAA and NASA as partners in the project. As many as 13 different aircraft made sampling flights, including a big DC-6 loaned from National Hurricane Research Project, and an F-102 and an F-106, two of the Air Force’s hottest interceptors. While understanding tornadoes and squall lines remained the major scientific goal, the other government partners also sought to understand how delta-winged aircraft behaved in thunderstorm conditions.

Three of the "Rough Rider" airplanes that joined the newly renamed National Severe Local Storms Research Project for the 1960 season. The Air Force's F-102 and F-106 interceptors were some of the first delta winged aircraft used in regular service. The wing shape enabled speeds above mach 2, but its stability in turbulent skies was unknown. Image from Brent B. Goddard, “The Development of Aircraft Investigations of Squall Lines from 1956-1960,” Report No. 2, National Severe Storms Project (US Weather Bureau, 1962): p. 9.

What did the project achieve? The planes transmitted data in real time to the Severe Local Storms Forecast Center (abbreviated SELS, which later became the NSSL in Oklahoma). Revisions to forecasts were made based on the data sent from the plane. Data from TRAP flights was analyzed by the pioneering tornado researcher Ted Fujita in his study on the structure and movement of a dry front in 1958. But overall, the project was not particularly successful. As meteorologist and SELS alum Joe Galway assessed it in 1992, “No new forecast methods were developed by the project or from the volumes of data obtained."

But the more important legacy came in research management. As Newton recounted in an oral history interview:

The sad part of that was that after the expenditure of what I suppose much have been a couple of million dollars on these programs, they couldn't find $20,000 to process the data. And that's something that happily, that kind of situation is improved. Nowadays when funding includes processing and working on the data rather than just taking it.

It's a good reminder that analysis and the human brains that do it are the true easily overlooked resources in meteorology.

Learn More:

- T.H. Fujita, "Structure and Development of a Dry Front," Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 39 (1959): 574-582.

- Joseph G. Galway, “Early Severe Thunderstorm Forecasting and Research by the United States Weather Bureau,” Weather and Forecasting, vol. 7 (December 1992): 564-587.

- Brent B. Goddard, “The Development of Aircraft Investigations of Squall Lines from 1956-1960,” Report No. 2, National Severe Storms Project (US Weather Bureau, 1962). (Top image of P-38 is printed on p. 6)

- Oral history interview with Chester Newton, AMS/UCAR Tape Recorded Interview Project, March 13, 1990.