George Washington Carver observes the Great Miami Hurricane, 1926

Weather data from Tuskegee, Alabama for September 1926, observed by George Washington Carver, recorded on Weather Bureau Form 1009. Image produced by the NOAA Central Library Data Imaging Project, with funds from the NOAA Climate Database Modernization Program (CDMP), National Climatic Data Center, Asheville, NC.

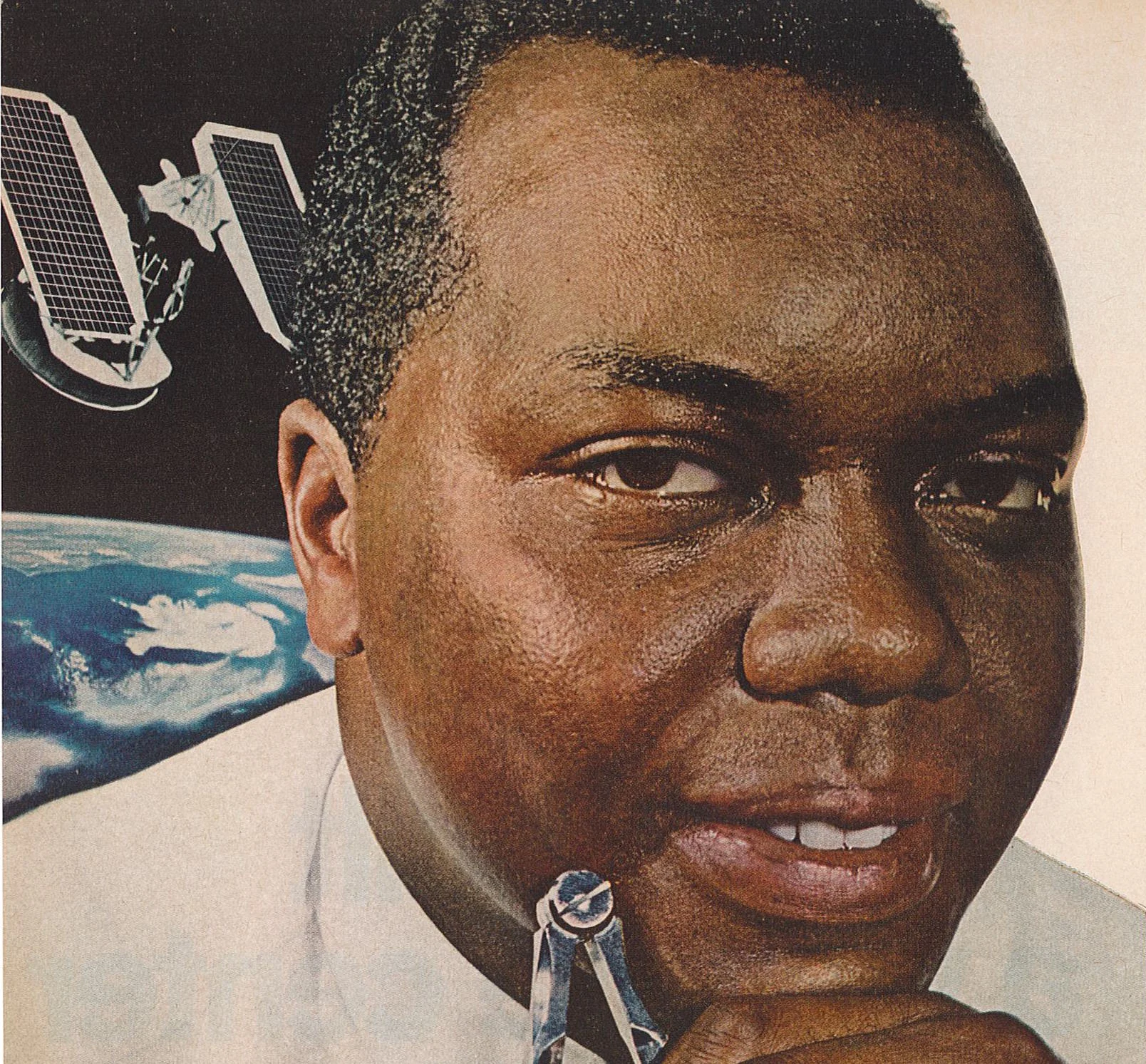

Today, as part of Black History Month, I’m featuring the weather observations made by George Washington Carver, most famous as the chemist and botanist who promoted peanuts from his lab at the Tuskegee Institute. Carter was also a cooperative observer for the US Weather Bureau from 1899 to 1932.

The picture shows Weather Bureau form 1009, the Cooperative Observer’s Meteorological Record, reporting Carver’s observations for September 1926. September 1926 is notable because of the passage of a hurricane, which famously lashed Miami on September 18th. The storm passed across the Florida peninsula and later made landfall twice more, in Alabama and Mississippi, before dissipating. Coming at the end of a real estate boom in Florida, the storm caused more estimated property damage, when adjusted for relative wealth at the time, than any other hurricane in US history.

Carver himself did not remark upon the storm, though the evidence of its passage is clear from his entry for September 20th, when he recorded nearly 3 inches of rain in 24 hours. As was customary for Carver, his remarks addressed the impact of the month’s weather on particular crops. “The month has been a little too wet for cotton, but fine on late corn, potatoes, and fall gardens.”

These particular records were carefully digitized and made accessible because they are connected to Carver. Carver was both a human being and a complicated public symbol, interpreted and celebrated by diverse groups of people in support of very different ends. Carver biographer Linda McMurry notes that Carver’s career “was either proof of the ability and intelligence of Afro-Americans or an indication that slavery and segregation could not have been too bad if they produced a Carver.” As she continues, “He became the Peanut Man, a stereotype of an accommodationist achiever that served many symbolic needs” (p. viii).

So how should we make sense of his contributions to meteorology?

On one hand, recording the weather does not seem particularly central to the work that made Carver notable. The weather reporting station is barely mentioned in books about Carver. Mark Hershey’s recent “environmental biography” only notes the weather station as part of a list of duties that were added to Carver’s heavy teaching load and responsibility for managing the Institute’s farm (p. 87). Perhaps it was a chore that Carver didn’t much desire.

On the other hand, the weather station represented recognition and a sign of respect from a government not notably interested in Negro institutions. (In the midst of Carver’s time as a cooperative observer, President Woodrow Wilson segregated the Federal civil service, eliminating thousands of middle class and professional jobs for black people.) The Federal Weather Bureau had entrusted Carver and the Institute with the responsibility to contribute to creating the climatic record. Carver took his duty seriously, and produced decades of reliable records.

I read Carver’s meteorological work as illustrative of a project much bigger than even Carver’s outsized symbolic significance. Carver’s meticulous weather observations are part of a vast archive of daily weather observations carefully made by thousands of volunteers across the United States. Created primarily to benefit agriculture, the cooperative observer program brings a degree of fine detail to the construction of the American climatic record since the 1880s. Collectively, the forms produce a remarkable data set and a tribute to the dedication of amateurs and volunteers in the production of science.

(And for the juvenile in all of us, George Washington Carver is my answer to the question, “Who made George Washington’s wooden teeth?”)

Learn More:

- “George Washington Carver and Tuskegee Weather Data,” NOAA Central Library, Silver Spring, Maryland.

- Blake, Eric S.; Landsea, Christopher W.; Gibney, Ethan J. (2011). "The Deadliest, Costliest, and the most intense United States Tropical Cyclones from 1851 to 2010 (and other frequently requested hurricane facts)." NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS NHC-6.

- Linda O. McMurry, George Washington Carver: Scientist and Symbol (Oxford University Press, 1981).

- Mark D. Hersey, My Work Is That of Conservation: An Environmental Biography of George Washington Carver (University of Georgia Press, 2011).

Image Source:

Weather Bureau Form 1009, reporting weather observations from Tuskegee, Alabama for September 1926, completed by George Washington Carver. Image produced by the NOAA Central Library Data Imaging Project. PDF reproduction of the original form at:https://docs.lib.noaa.gov/rescue/gw_carver_tuskegee/1926_sep.pdf