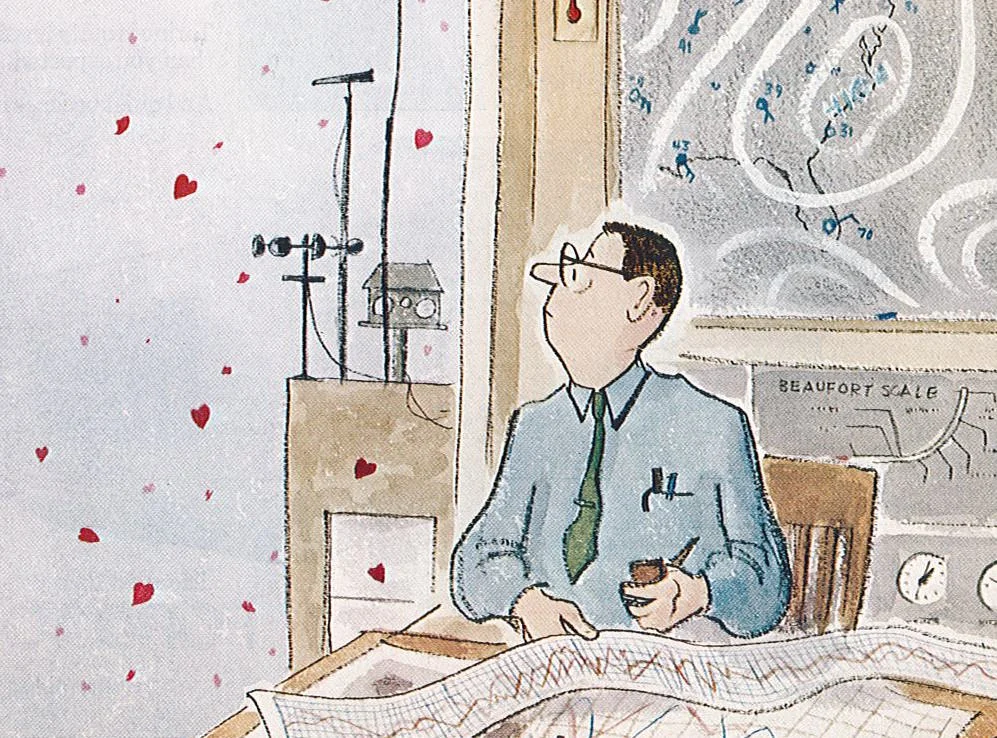

Valentine Meteorology, 1972

Drawing by James Stevenson, The New Yorker, February 12, 1972.

For Valentine’s Day, I thought I’d share a cheerful image from 35 years ago. A meteorologist looks up from his chart, surprised to see a snow of hearts out the window. This cover image was drawn by James Stevenson, the longtime New Yorker cartoonist and prolific children’s book author. He started at the New Yorker as a “gagman" in 1956, selling punch lines to other cartoonists for $75 each. "I wasn't supposed to tell anyone what I did,” he told the New York Times. “Cartoonists wanted people to think they were funny. If someone did ask what I did for The New Yorker, I'd just say, 'I don't know.'"

As an artist noted for “his loose drawings of the perplexed middle class,” Stevenson’s drawing offers chance to reflect on the sociology of meteorology.

Most meteorologists are a highly specialized kind of office worker. While some atmospheric scientists do spend stretches in the field, meteorologists generally labor in climate-controlled spaces, largely insulated from the weather they describe and the effects it has upon exposed bodies. They sit at desks, using pencils, paper or computers. Sociologist Gary Alan Fine calls forecasters “authors of the storm,” noting how they translate models of the weather into texts. Like other office workers, they produce value by manipulating symbols and words. Along with service work, office work grew dramatically in the United States during the 20th century, as mechanization displaced many kinds of farm work and automation transformed manufacturing during the later decades.

Meteorologists, like physicists, were part of the great growth of the American middle class during the middle decades of the 20th century. They expected to make extended careers within steady bureaucratic organizations, arranging their lives around a nuclear family, home ownership, and a regular commute to work. Like American intellectuals more generally, the mid-century meteorologists’ self-image was “solidly middle class, a man at a desk, married, with children, living in a respectable suburb,” in the words of sociologist C. Wright Mills. It’s useful to keep that self-image in mind when thinking about why white men are substantially over-represented in atmospheric science.

Learn More:

· Sarah Boxer, “A Gaggle of Cartoonists, but It's Not All Smiles; At a New Yorker Exhibit, Some Artists Revere the Old Days. Others Don't,” New York Times, February 14, 2000.

· Gary Alan Fine, Authors of the Storm: Meteorologists and the Culture of Prediction (University of Chicago Press, 2007).

· David Kaiser, "The Postwar Suburbanization of American Physics," American Quarterly 56 (December 2004): 851-888.

· C. Wright Mills, White Collar: The American Middle Classes (New York: Oxford University Press, 1951): 156.

Image Source:

Drawing by James Stevenson, cover of The New Yorker, February 12, 1972. Image scanned from a paper copy in my personal collection.