The Path of History, 1943

Even the word meteorology was unfamiliar to many men drafted into the military during World War II. One apprentice meteorologist remembered trying to convince his family he wasn't training to read gas meters. Introductory textbooks had to explain what meteorology was, and how it developed.

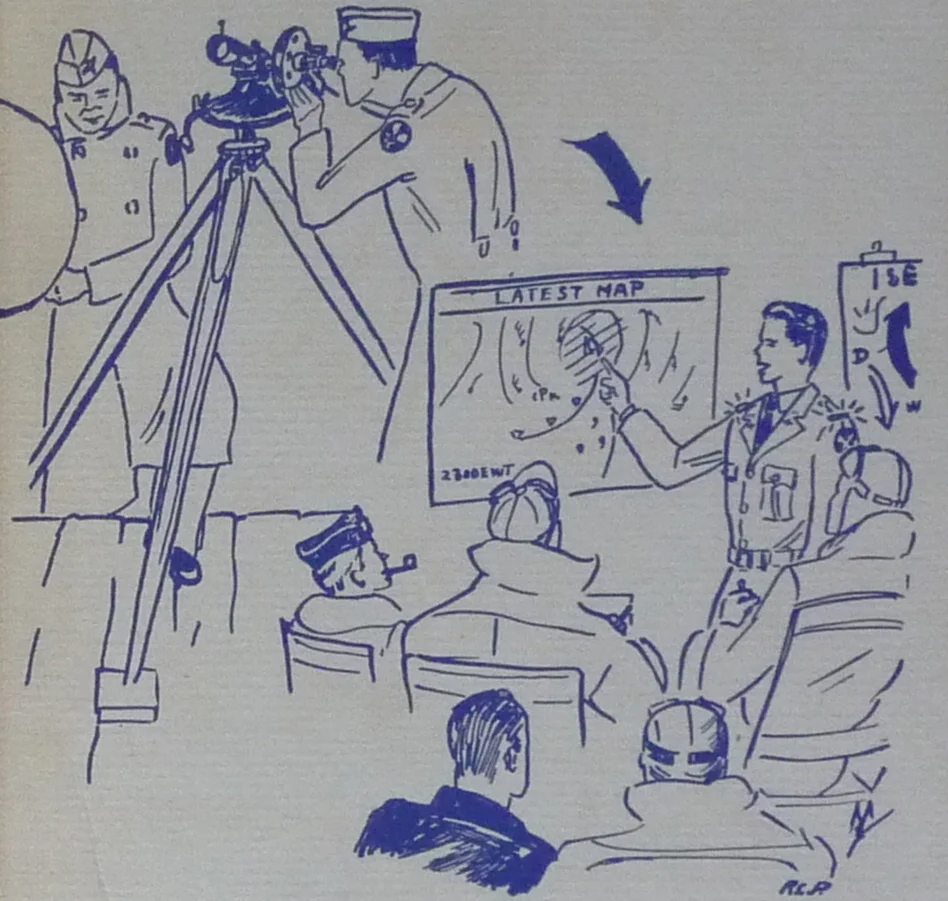

One book took an unusual approach to this challenge. This picture comes from An Illustrated Outline of Weather Science, a textbook written for US Navy aerographers in training. (Dating back to World War I, the US Navy insisted on using "aerography," meaning the charting of the upper air, to describe the work of weather observers.) In the introductory chapter, author Charles Barber sought to orient his readers within the history and future of their trade. New techniques from the 1930s like isentropic analysis and venerable tools like the synoptic chart followed from the insights of great minds like Robert Boyle, Evangelista Torricelli, and Benjamin Franklin, while the path of meteorological development led ultimately to that Valhalla of perfect long-range prediction and weather control.

These kinds of dreams about meteorology’s glorious future occasionally appear in the prefaces and introductions of meteorological textbooks from the 1940s, though wartime courses tended to focus on practical skills like air mass analysis and launching radiosondes,

I love this picture because the visual metaphor conveys such a distinctive philosophy of science. Science begins when the hand of reason uncurtains our eyes, and ends in power over nature. The path from superstition to weather control is long and winding, but also clear. There are no dead ends, no confusion or surprises. It is a process of cumulative progress where each advance leads towards a peak beyond which no further ascent is humanly possible.

But who walks this path? In this picture, the history of science is reduced to a series of instruments, theorists, and techniques. There is no mention of society or politics, war or passion, none of the complexities that accompany the production of knowledge by human beings.

This isn't the only way to understand science's history. Imagine this image in contrast with the non-progressive philosophy of science advanced by Thomas Kuhn twenty years later, where scientific revolutions wipe away accumulated understandings of experiments, replacing them with new interpretative paradigms radically disconnected from previous theories. What would a cartoon of Kuhn's vision look like?

Learn More:

· Kristine C. Harper, Weather By The Numbers: The Genesis of Modern Meteorology (MIT Press, 2008): “The War Years,” pp. 69-90.

· Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (University of Chicago Press, 1996 [1962]).

Image Source:

Unsigned cartoon, in Charles William Barber, An Illustrated Outline of Weather Science (New York: Pitman Publishing Co. 1943): p. 3.