The Original Storm Named Maria, 1941

The original storm named Maria wasn't a hurricane. It wasn't even real. But it changed the way we talk about weather, and it still explains how severe weather impacts the technologies we rely on.

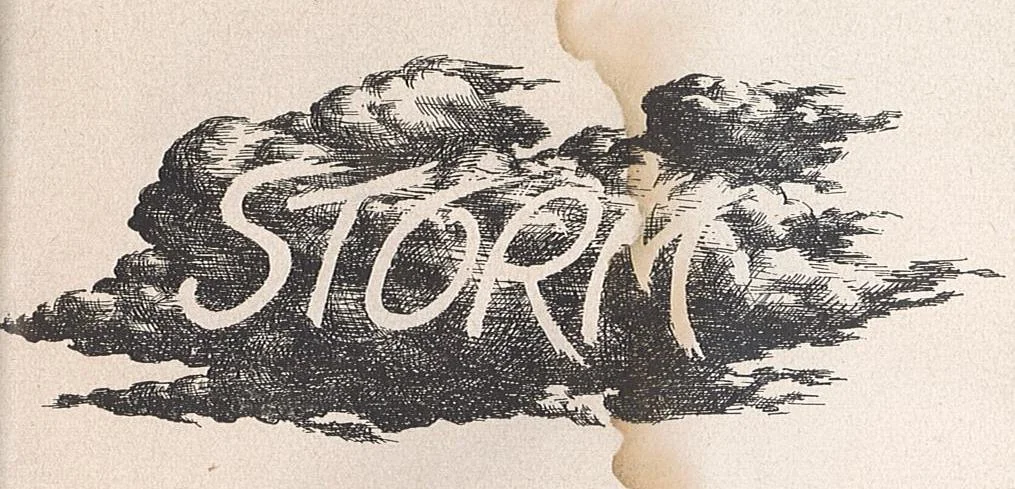

George R. Stewart published Storm in 1941. It’s a remarkable novel. Most of the people don’t have names, only job titles. The human characters are flat and change little through the story. But they're not the point. The central character is Maria (pronounced ma-rye-ah), a winter storm that lashes California. The book is really the biography of an extra-tropical cyclone, and it's popularity helped to establish naming storms as a public practice.

Stewart explained storm formation using the theories developed by the Bergen School, which were coming into American meteorological practice during the 1930s. "The line of the Polar Front becomes sharply marked--cold polar air to the north, warm tropical air to the south. And along the Front, like savage champions struggling in a death grapple, the storms move in unbroken succession." This struggle was further dramatized in a picture drawn for the Boy Scouts by Donald A. Smith. (Source: Boy Scouts of America, Weather, merit badge series, 1943. p. 7)

Born as "a hesitant eddy" at the frontal boundary between a polar and a tropical air mass, the incipient storm is privately named Maria by the Junior Meteorologist in San Francisco. He tracks her across the Pacific as he plots weather observations on the synoptic map he draws each day. The J.M. watches her low pressure center deepen and her power grow, marveling as her development matches the models in his textbooks.

The Junior Meteorologist at his synoptic map. "Not at any price would he have revealed to the Chief that he had christened each new-born storm with a girl's name. ... He considered a moment, and thought of Maria. ... He found himself smiling, wishing the baby joy and prosperity. Good luck, Maria!"

The action intensifies as Maria nears land. When the Weather Bureau issues warnings of the impending storm, into action spring the operators of roads and levees and airports and communications systems. They struggle to keep mountain passes open, to restore electricity as lines break, and choose when to open dams, sacrificing some areas to save others from greater disaster. People react to the weather in different ways. Some adapt, others try to force through with their previous plans, sometimes with fatal results.

Maria dies on its eleventh day, its stores of moisture from the tropical sea exhausted upon the mountains, "the air which had composed her now turned to new courses and revolved around other centers of activity." It had affected every person in the region, though it was not "catastrophic or even unusual."

The book explores how infrastructure mediates our relationship to nature. Stewart spent long hours talking with the people whose job is to keep infrastructure functioning as much as possible, whatever the weather. It's the only book I know of that deeply explores the effects of weather on the whole range of technological systems we rely upon.

Storm had a long career in popular culture. The book was a best-seller during World War II; a selection of the Book of the Month Club, that commercial enterprise that catered to middle brow readers seeking books that were both entertaining and improving. The book inspired Alan Lerner and Frederick Loew's song “They Call the Wind Mariah,” in the musical Paint Your Wagon. Disney adapted Storm for TV and it aired nationwide in 1959, though I can't find the episode anywhere today. Apparently singer Mariah Carey was named for the fictional storm, too.

The Boy Scouts also loved it. Excerpts made up about half of the Weather merit badge study manual used from 1943 until 1963, entertainingly illustrated by Don A. Smith.

According to a Weather Bureau pamphlet written in 1963, it was during World War II that the practice of using a girl's name to identify a storm "became widespread in weather map discussions among forecasters, especially Air Force and Navy meteorologists who plotted the movement of storms over the wide expanse of the Pacific Ocean." The Weather Bureau began naming hurricanes after women in 1953. Protests against the obvious sexism of that practice led the NWS and WMO to add male names in 1979. The Weather Channel began naming significant extra-tropical winter storms in 2012, leading to controversy amongst meteorologists.

The controversies over naming obscure the deeper importance of Stewart's book and its subsequent adaptions. Published at a time when air mass analysis and frontal mapping was still novel, Storm helped transform how ordinary Americans understood weather. Stewart made accessible the synoptic perspective that meteorologists used in forecasting. He crafted a story out of the complex images on a weather map, narrating what those isobars and fronts meant for the surrounding air, as well as for the people underneath. Today this is the work of TV weathercasters, but the foundation for this kind of communication began in the humanities. It was a novel that taught readers to identify a storm as a unitary subject, a being that followed a life cycle and had a distinctive biography, and maybe even had a personality.

Learn More

George R. Stewart, Storm: A Novel (Random House, 1941). A second edition, with an introduction by the author, was published by the Modern Library in 1947.

Bernard Mergen, Weather Matters: An American Cultural History since 1900 (University Press of Kansas, 2008): 235-237.

Angela Fritz, "Would naming winter storms be a better idea if more organizations got on board?" Washington Post, September 22, 2015.

Image Sources

First Image: Endpaper of the first edition of Storm, a novel by George R. Stewart (Random House, 1941). Illustration is signed "Steinberg."

Later Images: Drawings by Donald A. Smith, used to illustrate Weather, a merit badge manual published by the Boy Scouts of America from 1943 to 1963.

All Images are scanned from texts in my personal collection.