Where Should Your Weatherman Go? 1976

Since weather forecasts are such a familiar presence in our lives, they make good foundations for advertisements. Last month, we saw at how Guinness used weather forecast lingo to sell beer. Sometimes advertisers use meteorology to connect us to something rather more obscure. Here, the Olin Corporation tried tying weather forecasts to hydrazine, a rocket fuel and plastic component. The connection was tenuous, but at least the artwork was striking.

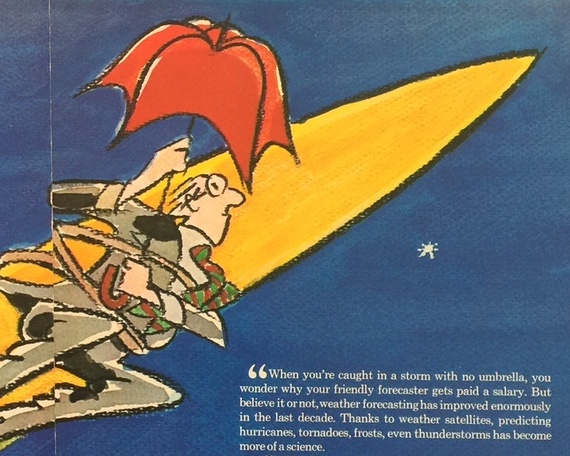

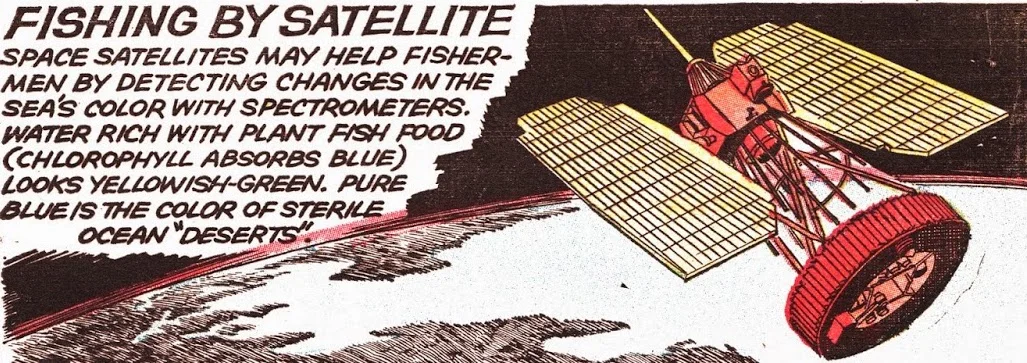

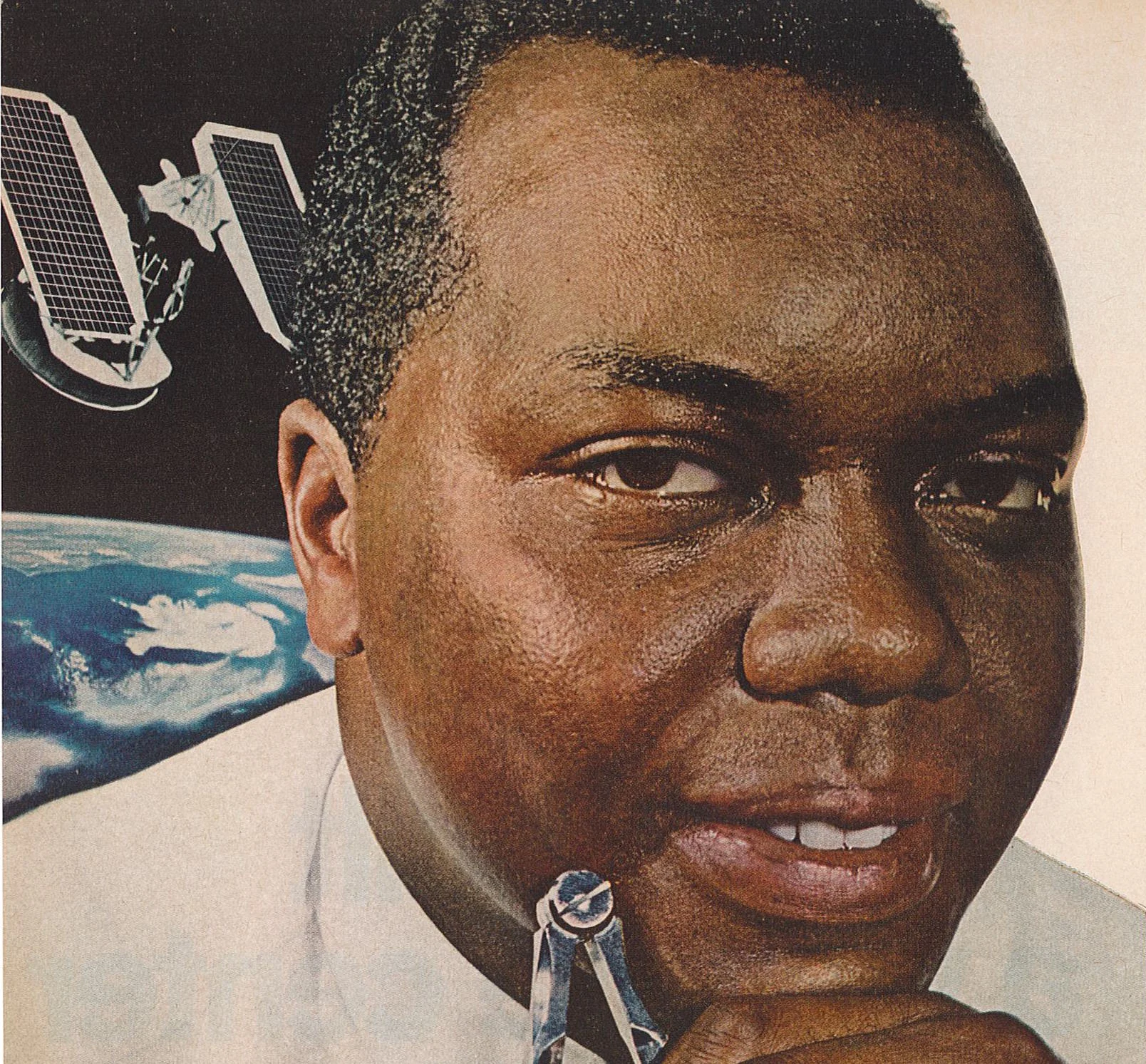

The premise here is when the weatherman blows a forecast, people want to blow him sky high. And that's just what hydrazine does. It fuels the rockets that launch weather satellites, as well as moon shots and probes sent to other planets.

The copy is equivocal about the accuracy of weather forecasts. "When you're caught in a storm with no umbrella, you wonder why the friendly weather forecaster gets paid a salary," the ad begins. "But believe it or not, weather forecasting has improved enormously in the last decade. Thanks to weather satellites, predicting hurricanes, tornadoes, frost, even thunderstorms has become more of a science." Yet after describing the many uses of hydrazine ("truly a wonder chemical") the ad ends with the wish that someone could just tell us if it's actually going to rain tomorrow.

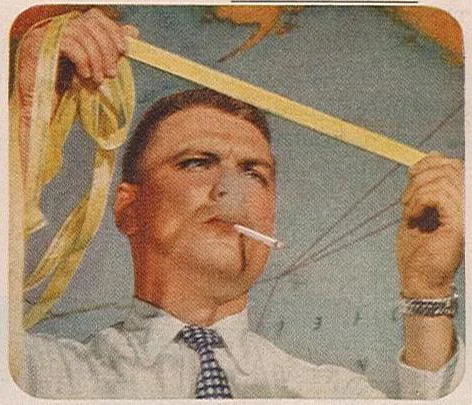

I'm interested in the depiction of the weather forecaster. He holds an umbrella as a symbol of his office, but notably absent are any signifiers of science, like an instrument, computer, chart, or test tube. (Though he does wear eyeglasses.) He is a middle-aged, balding, white man dressed in an ordinary suit with a loud tie. He's probably a television weathercaster, but could be a representation of government meteorologist with the National Weather Service. By age and appearance, he matches the demographic that dominated the weather cadet generation that pervaded meteorology from the 1940s to the 1980s.

Image Source

"Where should your weatherman go?" advertisement for Olin Corporation. Published in Fortune magazine, September 1976, pp 144-145. Digital image from a paper copy in Roger Turner's personal collection.