Space Weather Enterprise Forum, 2017

Swipsy tracks the Sun's emissions. Image credit: The emblem of NOAA/NWS Space Weather Prediction Center.

I spent much of yesterday at the Space Weather Enterprise[1] Forum in Washington, D.C. It was fascinating to see the work that an historical analogy did in framing the future of an important part of space science.

“We’re at the 1960 level,” Louis Uccellini said, “We’re right at the front end.” He was comparing the National Weather Service’s current space weather modeling capabilities to the historical development of “terrestrial weather” simulations. Back in 1960, operational weather forecasters had only been using computer-based numerical models for five years. The Weather Bureau didn’t forecast more than 4” of snow, and didn’t predict major east coast winter storms until they were actually developing, Uccellini said. Today, FEMA uses NWS products to preposition emergency assets 5 to 6 days in advance.[2]

As head of the National Weather Service, Uccellini oversees the NOAA/NWS Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC). “Swipsy,” as everyone pronounced it, is the operational office that issues forecasts, watches, and warnings about the electromagnetic environment between Earth and the Sun. When the Sun burps or breaks wind, SWPC alerts the engineers and managers who have to react.

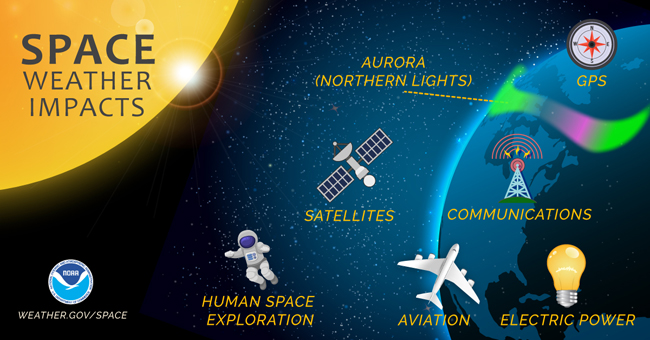

There is a surprisingly large number of industries concerned about space weather. Anyone who operates a satellite, or who depends upon a satellite for a vital service, needs to know about the space environment. Storms from the sun can disrupt radio communications, GPS signals, and remote sensing instruments, including those used for surveillance and intelligence gathering. Subscriptions to SWPC products have passed 50,000, and are increasing at about 200 per month. Users include emergency responders, major airlines, ocean drilling and oil exploration firms, the transport sector, and space operators. Power grid operators are also very interested, as currents induced solar storms can wreck transformers and cause major blackouts.

Image Credit: NOAA.

As Uccellini pointed out, the space weather enterprise has a very long way to go until people can depend upon it to prepare assets 5 days in advance. We’ll need to learn how to look inside the sun to get to that level. That means at least three things: understanding heliophysics much better; integrating knowledge of the sun’s fundamental processes into accurate forecasting models; and establishing a reliable observation network of satellites and Earth-based instruments that can monitor the sun on a long-term basis. Off the cuff, he estimated we’re only about 5% of the way to fully developed operational space weather system.

I left the conference pondering if we should expect space weather prediction to develop in the same way that terrestrial weather prediction did. Analogy is a powerful persuasive tool, but also radically simplifying. Terrestrial meteorology in 1960 was growing in the Cold War garden of earth sciences, showered in dollars provided by a government that valued stockpiling technical experts, and fertilized by cultural patterns that routed a great deal of brainpower and human capital towards the physical sciences. The garden doesn’t look like that today.

[1] “Enterprise” not in the Star Trek sense, but meaning all the diverse groups concerned with space weather, including businesses, government agencies, academic researchers, and the military. Diplomats from the State Department were there too, since space weather is a global phenomenon, and monitoring it requires international cooperation.

[2] Dr. Uccellini has a solid background for this kind of comparison. He’s co-written two volumes on Northeast Snowstorms for the AMS historical monographs series, as well as more than 60 scientific articles.