Weather Cadet Generation: William H. Rehnquist

William H. Rehnquist (middle row, second from right) was part of Flight D-2 when he studied math and physics in a pre-meteorology program at Denison College. Image Source: Tattoo, a yearbook by the 62nd Army Air Force Technical Training Detachment (Denison College, 1944). From my personal collection.

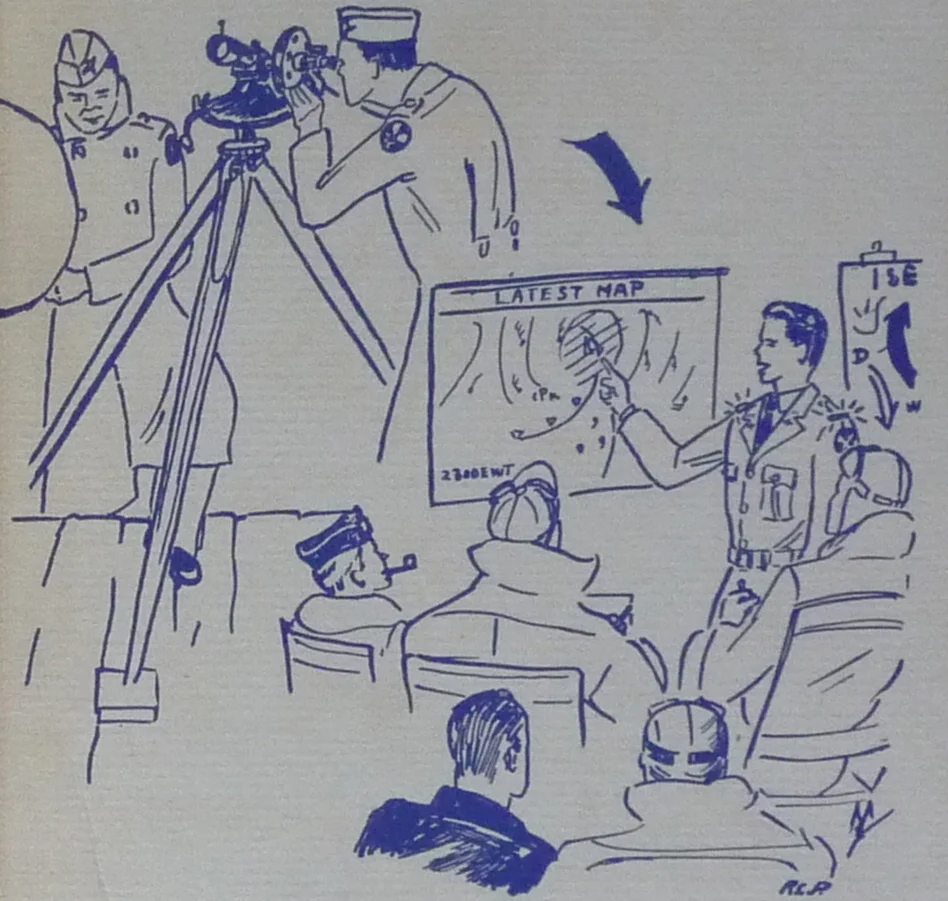

“Lazily stretched out on his bed with his patented eye-ear-nose sleeping bag over his head is Hubbs Rehnquist, that great liberal and crusader for the Wisconsin dairy farmer." The arch-conservative-even-at-19 future Chief Justice of the Supreme Court was learning math and physics at Denison College when his classmates teased him in their commemorative yearbook. He was part of a pre-meteorological training program begun early in World War II when it appeared there might not be enough college graduates to meet the meteorological needs of the US armed forces. [1]

Rehnquist had volunteered for the pre-meteorology program. When he enlisted March 4, 1943, he changed his middle name from Donald to Hubbs. Rehnquist’s future clerk, now Chief Justice John Roberts, recounted that Rehnquist’s mother’s numerologist said he would have a successful career if his middle initial was H.

W. Hubbs Rehnquist found the college level math and physics tough going. “I had a good academic record in high school, but had never gone beyond plane geometry and had no physics,” he remembered much later. “I was hanging on by the skin of my teeth.” [2]

Rehnquist served as coeditor of Tattoo, the training detachment’s commemorative yearbook, the source of these images of student life in the pre-meteorology program. The cartoon was drawn by Rehnquist's classmate Robert T. Davis.

The military realized it would need fewer meteorologists than originally thought and shut down the pre-meteorology program February, 1944. Trainees could choose between continuing into office candidate school or serving as enlisted men. Hubbs made the unconventional choice; he eventually rose to sergeant as an enlisted weather observer.

He was posted first to Will Rogers Field in Oklahoma City, where he launched weather balloons and reported observations via teletype in support of Army Air Force training squadrons. Brief postings to Carlsbad, New Mexico and then Hondo, Texas inspired a lifelong love of the American Southwest.

A graphic similar to the World War II-era postcards available for sale near Rehnquist's first post at Will Rogers Field, Oklahoma.

In the summer of 1945, Rehnquist, just 21 years old, was deployed to North Africa. He moved from air base to air base as military activity in Europe wound down, ending up in Casablanca. The situation there was too good to be true, he told the Washington DC chapter of the AMS in 2001: “Most of the weather facility had been turned over to French civilians to operate, since Morocco was French territory and they would have to take over when the last American troops left Cazes. So the responsibilities of the Weather Squadron were minimal.” Discharged in late winter 1946, he felt he’d made a modest contribution to allied victory; he took a curious lesson from the war: “I, and millions like me, learned to obey orders, and do what we were told.” [2]

After the war, he briefly studied politics at Harvard and finally buckled down at Stanford Law School, graduating first in his class, two spots ahead of future colleague Sandra Day O’Connor. Rehnquist’s education was paid for by the G.I. Bill, a powerful affirmative action program for white men. [3] A professor who had clerked for Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson secured an interview for Rehnquist, which led to the plum clerkship. [2]

As the Court debated Brown v. Board of Education, Rehnquist wrote a brief for Jackson defending racial segregation. Rehnquist then went into private practice in Phoenix before joining the Nixon Administration in 1968. Richard Nixon nominated him for the Supreme Court in 1971; Ronald Reagan selected this man who “made it respectable to be an expedient conservative on the Court” to be Chief Justice in 1986. [2]

As a justice, Rehnquist opposed affirmative action programs that benefitted women and racial minorities. He consistently favored government and businesses over individual rights, eroding the expansion of liberty that had marked the Warren court. His decisions and administrative work made it easier for the government to execute people, and he repeatedly (though not always) joined opinions that tried to limit the rights of gay people. He also orchestrated the majority decision in Bush v. Gore that stopped the 2000 presidential recount, thus directly enabling the Bush presidency, and indirectly leading to the deaths of more than 1 million Iraqis.

One law professor described Rehnquist's legacy as "a thick jurisprudence hostile to popular democracy and protective of race privilege and corporate power." [4]

During a talk describing his experiences in meteorology to the District of Columbia chapter of the AMS in October 2001, someone asked him about his decision to leave meteorology for law. Rehnquist quipped that liked to think the switch improved both professions. I think not.

Learn More

- Tattoo, a yearbook by the 62nd Army Air Force Technical Training Detachment (Denison College, 1944).

- John A. Jenkins, The Partisan: The Life of William Rehnquist (New York: Public Affairs, 2012). Rehnquist's meteorological experiences are described in Chapter 2.

- Ira Katznelson, When Affirmative Action was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America (W.W. Norton, 2006).

- Linda Greenhouse, “William H. Rehnquist, Chief Justice of Supreme Court, Is Dead at 80,” New York Times, September 4, 2005.