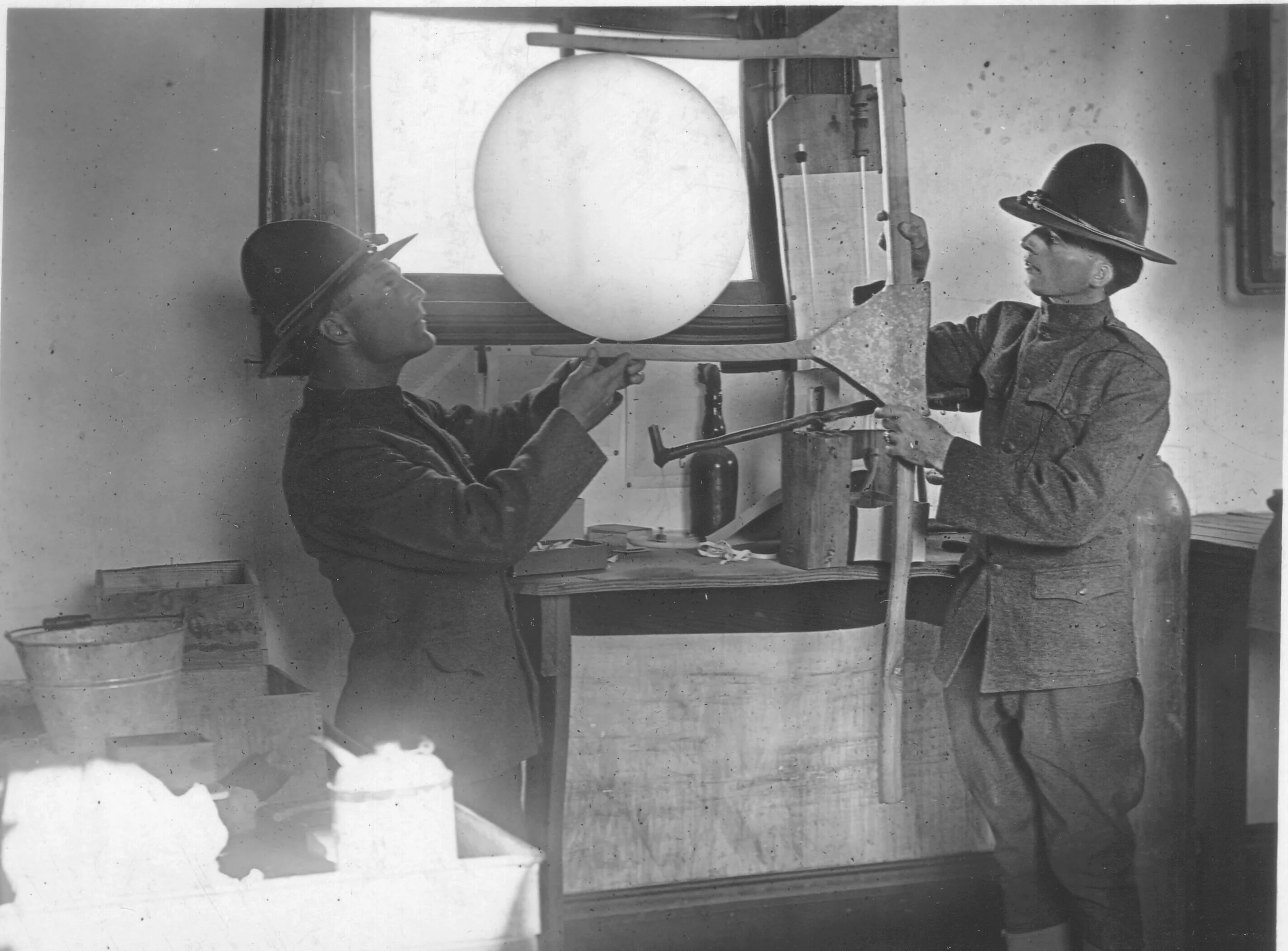

Meteorologists for the Great War, 1918

Privates Bly and Greening measure a weather balloon to ensure it is properly filled with hydrogen. Photo by A.W. Atkinson, US Army Signal Corps. Courtesy of the US Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle, PA.

“More meteorologists are needed,” wrote Charles F. Brooks, a professor at Yale, in June, 1918. World War I had placed heavy demands on meteorologists. New weapons like poison gas, ballistic artillery, and aviation required detailed observations of the weather, especially of the structure and movement of the atmosphere above the battlefields of France. As the US Army mobilized hundreds of thousands of troops, it became clear that there were not enough trained meteorologists and weather observers to fulfill the Army’s needs.

The Army Signal Corps established a temporary School of Meteorology at College Station, Texas. According to the lead instructor, Weather Bureau forecaster and Johns Hopkins University Professor Oliver Fassig, “practically the entire Civil Engineering Building has been given us for school purposes.” Over 300 physicists, engineers and other technical specialists underwent an 8-week course in meteorology. In addition to studying meteorological theory, they learned how to inflate pilot balloons to precise weights, track them using theodolites, and convert raw observations into useable data on wind velocities at various altitudes. The group photo below shows some of the students on Campus at Texas A&M, possibly observing the rise of a pilot balloon. Charles Brooks, wearing a civilian suit and standing behind the weather vane, taught the course on meteorological theory.

Professor Charles F. Brooks (center, behind anemometer) and other faculty and meteorological trainees observe the ascent of a weather balloon. Photo by A.W. Atkinson, US Army Signal Corps. Courtesy of the US Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle, PA.

But the American meteorological enterprise was small and not easily expanded in 1918. “Instruments cannot be procured, at least not in a hurry,” Fassig complained to the Chief of the Weather Bureau, asking to borrow even defective equipment and instruments ordinarily used only for demonstrations.

Privates Bauer and Keyte prepare to use a theodolite to track a weather balloon. Photo by A.W. Atkinson, US Army Signal Corps. Courtesy of the US Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle, PA.

These photos are part of a series of about 30 taken by Private A.W. Atkinson, one of the members of the meteorological training detachment. They are preserved at the US Army Heritage and Education Center, in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. I thank Kristine C. Harper for bringing these to my attention and sharing her scans with me.

Learn More:

· Charles C. Bates and John F. Fuller, America’s Weather Warriors, 1814-1985 (Texas A&M Press, 1986)

· Charles F. Brooks, “Notes on Meteorology and Climatology,” Science, New Series, v. 47, No. 1223 (June 7, 1918): P. 565-567.

· Oliver L. Fassig to Chief of the United States Weather Bureau, June 6, 1918. US Army Heritage and Education Center, in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Image Source:

US Army Signal Corps. Courtesy of the US Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle, PA.